As far as I know, nobody is funding studies of the genetics of racial differences in intelligence. Although research is being carried out on the genetics of intelligence generally, and the genetics of different racial groups generally, for some reason nobody makes the link.

An exception is Davide Piffer, who as far back as 2014 suggested a possible approach: find any of the genetic variants associated with intelligence, however weak and inconsistent they may be, and then look up the published literature to see how frequent those variants are in any racial group. If there are many such positive variants in a group they will be bright, and if there are fewer such positive variants they will be less bright.

Here is the first account I gave of Piffer’s work in 2014:

http://drjamesthompson.blogspot.co.uk/2014/05/lci14-davide-piffer-human-polygenic.html

So far, this post has drawn no comments. However, it might turn out to be a significant step forwards.

The next account was in 2015 showing the pattern based on 9 GWAS hits:

http://drjamesthompson.blogspot.co.uk/2015/09/gwas-hits-and-country-iq.html

Now, in the wake of the most recent publication by Davies 2016 which I covered in my last post

http://drjamesthompson.blogspot.co.uk/2016/04/genetics-of-mental-ability-greater-power.html

Davide Piffer has taken the data from that very paper in order to extend his work on racial differences.

Recent polygenic selection for educational attainment

The genetic variants identified by two large GWAS of educational attainment were used to test a polygenic selection model.

Average frequencies of alleles with positive (Beta) effect on the phenotype (polygenic scores) were compared across populations and racial groups using data from 1000 Genomes and ALFRED. Strong correlations between polygenic scores and population IQ were found (r>0.8). Moreover, the polygenic score obtained from the two independent GWAS exhibited a strong correlation (r= 0.83), even after pruning for linkage disequilibrium.

Factor analysis revealed that most alleles loaded on a single factor, which in turn was strongly correlated to population IQ.

Polygenic and factor scores survived control for phylogenetic autocorrelation, although the latter’s net effect on population was stronger (Betas= 0.361 and 0.861, respectively).

Results obtained from ALFRED data were similar and revealed a peak in polygenic and factor scores among East Asians (60.8% and 1.06, respectively) and a nadir among Africans and Native Americans (44.1% and 0.493).

Geographic distance from Eastern Africa (assuming an origin of modern humans there) was only weakly predictive of factor and polygenic scores (r= 0.21-0.29).

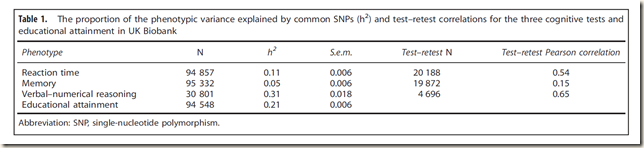

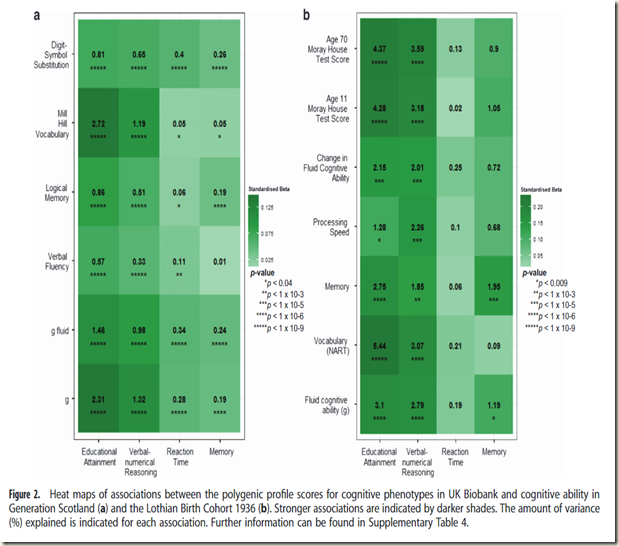

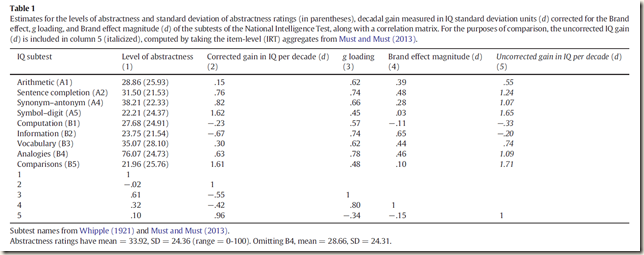

The aim of this study is to replicate the studies by Piffer (2015, 2013) that educational attainment and cognition GWAS hits have different frequencies across populations and thus, were subject to different selection pressures. To this end, the hits from the latest GWAS on educational attainment (Davies et al., 2016) will be used in the analysis. This GWAS was carried out using the UK Biobank sample (N=100K+). Over a thousand SNPs reached genome-wide significance (P< 5 x 10-8), but after controlling for linkage disequilibrium (Genotypes were LD pruned using clumping to obtain SNPs in linkage equilibrium with an r2<0.25 within a 200 bp window), a few independent signals were identified (Davies et al., 2016).

https://figshare.com/articles/Polygenic_selection_on_educational_attainment/3175522/1

The boxplot below shows the major continental groups as derived from the 1000 genomes data.

| Population | Education attainmentP.S, I.S.(Davies et al., 2016). N=14 | All_Ed_Att_2016. N=942 | PS All Ind. (N=16) | Factor All Ind. | IQ |

| Afr.Car.Barbados | 0.419 | 0.411 | 0.361 | -1.385726617 | 83 |

| US Blacks | 0.447 | 0.428 | 0.387 | -1.040795929 | 85 |

| Bengali Bangladesh | 0.516 | 0.566 | 0.461 | -0.009509494 | 81 |

| Chinese Dai | 0.610 | 0.652 | 0.564 | 1.229103674 | |

| Utah Whites | 0.493 | 0.467 | 0.461 | 0.385060759 | 99 |

| Chinese, Bejing | 0.671 | 0.682 | 0.636 | 1.614207102 | 105 |

| Chinese, South | 0.648 | 0.674 | 0.606 | 1.399490512 | 105 |

| Colombian | 0.500 | 0.512 | 0.462 | 0.155020855 | 83.5 |

| Esan, Nigeria | 0.416 | 0.417 | 0.362 | -1.517446756 | 71 |

| Finland | 0.560 | 0.560 | 0.524 | 0.873423777 | 101 |

| British, GB | 0.526 | 0.494 | 0.499 | 0.568096086 | 100 |

| Gujarati Indian, Tx | 0.498 | 0.550 | 0.457 | 0.064904594 | |

| Gambian | 0.438 | 0.398 | 0.381 | -1.3799435 | 62 |

| Iberian, Spain | 0.512 | 0.488 | 0.481 | 0.4310518 | 97 |

| Indian Telegu, UK | 0.510 | 0.583 | 0.457 | 0.030182344 | |

| Japan | 0.652 | 0.679 | 0.625 | 1.422186914 | 105 |

| Vietnam | 0.618 | 0.642 | 0.579 | 1.25233893 | 99.4 |

| Luhya, Kenya | 0.425 | 0.428 | 0.372 | -1.438642624 | 74 |

| Mende, Sierra Leone | 0.416 | 0.421 | 0.364 | -1.40422492 | 64 |

| Mexican in L.A. | 0.499 | 0.555 | 0.455 | 0.01771732 | 88 |

| Peruvian, Lima | 0.477 | 0.559 | 0.430 | -0.00789958 | 85 |

| Punjabi, Pakistan | 0.511 | 0.564 | 0.475 | -0.049972973 | 84 |

| Puerto Rican | 0.489 | 0.480 | 0.451 | 0.026710407 | 83.5 |

| Sri Lankan, UK | 0.506 | 0.564 | 0.454 | 0.070996352 | 79 |

| Toscani, Italy | 0.501 | 0.486 | 0.458 | 0.265676967 | 99 |

| Yoruba, Nigeria | 0.421 | 0.417 | 0.372 | -1.572005998 | 71 |

The analysis of independent signals from two different GWAS revealed a significant overlap across two genomic datasets. Using ALFRED and 1000 Genomes, the Rietveld et al. (2013) and Davies et al. (2016) polygenic scores were strongly correlated (r= 0.62 and 0.83, respectively). Both sets of GWAS hits were strong predictors of population IQ. The polygenic score (N=14) computed from the new independent hits (Davies et al., 2016) had a strong correlation to population IQ (r= 0.82). Similar correlation was observed for the polygenic score created by combining all the independent hits (free of LD) from the two publications (N=16): r=0.843 with population IQ.

Factor analysis produced a factor that even more strongly correlated to population IQ (r= 0.89) and survived control for spatial autocorrelation. Indeed, the predictive value of this factor was not affected by partialling out Fst distances. The high Beta value (B=0.82) and the null effect of Fst distances (B= -0.16) are suggestive of polygenic selection on these SNPs, independent of noise due to migrations or drift.

Comparisons of mean frequencies across racial groups via one-way ANOVA produced either non significant or marginally significant results, but the addition of new GWAS hits is needed to provide a definitive picture.

A limitation of this study is the reliance on GWAS hits for a complex phenotype such as educational attainment, which shares the majority of additive genetic variation with general intelligence, but also other personality and health-related traits (Krapohl et al., 2014 and 2015).

Another more obvious limitation is the small number of (independent) SNPs used for this analysis. More GWAS of intelligence or educational attainment are needed to shed light on worldwide patterns of polygenic selection on cognitive abilities.

As the author says, this can only be considered a first step. However, the method has the merit of simplicity: if some variations in the genetic code are associated with intelligence, then groups that have more of those variations ought to be more intelligent. If they are not, then the link between these variants and intelligence can be called into question. Of course, it is possible that these are not the most important variants, and that they differ between racial groups for trivial reasons. If so, then the observed associations are an unusual coincidence. I think this is a method to watch. When even more genetic signals of intelligence are identified, however weak and tentative, this approach can be put to the test, and then improved or discarded.